If you claim to be a smart investor, then you cannot view your investment solely on the basis of the return it can generate. You have to simultaneously check out the tax implications of that investment.

Is it an avenue that will help you save tax like the Public Provident Fund (PPF) or an Equity Linked Savings Scheme (ELSS)? Would you have to pay tax on the interest earned (fixed deposit) or is it tax free (PPF)? Would dividends be taxed or not? Would you be taxed if you made a profit on a sale (stocks, mutual funds or real estate)?

An investment made may seem fantastic, like a fixed deposit with an absolutely great interest rate. But since the interest earned is taxed, the yield drops. And, if you fall in the highest tax bracket, that is going to be your tax impact. All of a sudden, the investment sucks!

What we have done here is look at the tax implication on all investments made in mutual funds.

Where the tax angle is concerned, there are just two categories to consider - equity and debt. This should avoid any sort of confusion. Schemes that invest 65 per cent or more of their entire corpus in domestic equity (shares of companies listed in stock exchanges in India) are termed as equity schemes. The rest fall into the debt category.

Before we move on, let's just talk of one set of funds called the asset allocation funds. These funds have the mandate to be totally flexible in their asset allocation. They can move all their assets into equity or totally exit it, all at the discretion of the fund manager or a mathematically computed programme that takes the call. This makes their tax computation a bit difficult. Hence it is only at the end of the year that one gets to know where these funds have invested and accordingly determine their tax status.

Another area where we do have some ambiguity is in the case of arbitrage funds, which are categorized as "Hybrid: Arbitrage". These funds take advantage of a price mismatch between the cash market and the futures market. But, the asset allocation may also move between equity and debt as in the case of UTI SPrEAD. The average debt allocation has been in the vicinity of 68 per cent while equity has been around 6 per cent (March 2008 - August 2008). As on August 31, 2008, UTI SPrEAD had an equity allocation of 10.56 per cent, while the corresponding figures for JM Arbitrage Advantage and SBI Arbitrage Opportunities were 71.48 per cent and 71 per cent, respectively. JP Morgan India Alpha states in its Offer Document that this arbitrage fund should be treated as a debt fund.

GETTING A FIX ON CAPITAL GAINS

When an investor sells an asset and makes a profit, it is termed as a capital gain (capital loss should the reverse hold). This asset could be anything - home, land, stocks, mutual funds, fixed return instruments like fixed deposits, bonds and debentures, and even gold. The tax levied on this profit is called the capital gains tax.

Depending on how long you held the asset, it is broken up into Long Term Capital Gains (LTCG) and Short Term Capital Gains (STCG).

Where all mutual funds are concerned, LTCG comes into play if you sell your units after 12 months of holding. But, if you sell them within a year of buying, then STCG is applicable.

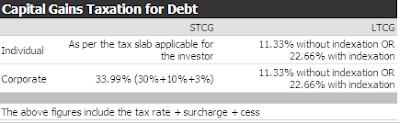

Equity

Where all equity mutual funds are concerned, the deal is identical for an individual or corporate.

The LTCG is not taxed. That's right, it is nil. So if you sell your shares or units of your equity fund after a holding period of a year, you pay absolutely no tax on the gain.But if you sell it before a year, then the STCG tax is 16.99 per cent. This includes the capital gains tax rate as well as the surcharge and cess (15%+10%+3%).

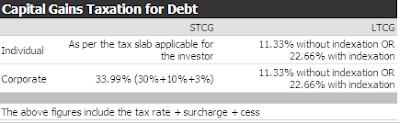

Debt

If you sell your debt fund before a year of holding, STCG comes into play. If you sell it after a year, then LTCG is relevant.

The good aspect with LTCG is that the income tax authorities give you the option to include the benefit of indexation. Indexation is the process by which inflation is taken into account when doing the tax calculation. This is excellent because it reduces the amount of capital gains and consequently the amount you end up paying as tax.

ARE DIVIDENDS TAXED?

There seems to be a lot of confusion concerning the Dividend Distribution Tax (DDT). It is a tax imposed only on the Asset Management Company (AMC) and not on the investor. However, the AMC will deduct the dividend tax from the money that will eventually go to the investors. So it's the investor that loses out in the end, not the AMC.

MAKING THE RIGHT CHOICE

Let's look at a basic dilemma facing investors: Is a growth option more viable or a dividend one? After looking at the tax implications, which one is the better option?

To answer this query, we will have to assume two scenarios, one where the investment is done for a period of less than 12 months, and the other for more than a year. This will enable us to better understand the short- and long-term capital gains impact.

Types of Equity Funds

Diversified: Funds that invest in Indian equity across sectors and market cap.

ELSS: Tax-saving funds that have a 3-year mandatory lock-in period.

Index: Such portfolios replicate the relevant index constituents. It also includes Exchange Traded Funds (ETFs).

Sector: Funds with a focus on a particular sector - FMCG, banking, auto, media, healthcare & pharma, technology, power.

Thematic: Focus on a theme like infrastructure.

Hybrid: Only the equity oriented ones.

Fund of Funds: Those funds that invest in the schemes of the other funds.

Types of Debt Funds

Medium Term: The maturity profile of the portfolio is more than 3 years.

Short Term: The maturity profile ranges from 1-3 years .

Ultra Short Term: Also termed as liquid funds, the maturity profile is less than 1 year.

Liquid Plus: 30% - 50% of the assets are in debt securities of maturity greater than 1 year, the balance maturity is less than a year.

Gilt: Short Term: The funds invest in government securities (G-Secs) with a maturity profile of less than 3 years.

Gilt: Medium-Long Term: G-Secs with a maturity profile greater than 3 years.

Floating Rate Short Term: Portfolio with floating rate debt instruments tilted towards short-term maturity.

Floating Rate Long Term: Portfolio with floating rate debt instruments tilted towards long-term maturity.

Hybrid: Those with an equity allocation of less than 65%.

Gold ETFs: Exchange Traded Funds take exposure to physical gold.

MIPs: With a max. equity exposure of 15%, their portfolio consists of bonds, CP, CDs, G-Secs and T-Bills.

International Funds: They invest in foreign equity, not domestic.

Fund of Funds: Those that invest in funds abroad do not fulfill the criteria of investing in domestic equity. FMPs:Fixed Maturity Plans are close-ended income schemes that invest in debt and money market instruments maturing in line with the tenure of the scheme.

IS AN STP WORTH IT?

In a Systematic Transfer Plan (STP), a fixed amount is switched from one scheme to another at regular intervals. In effect, it works out to be a combination of a Systematic Withdrawal Plan (SWP) and a Systematic Investment Plan (SIP).

A SWP is one where the mutual fund allows you to redeem units at regular intervals. A SIP, on the other hand, allows you to buy units periodically. Both the dates, and the amount to be withdrawn or invested, will be predetermined.

So how would a STP work? Let's say an investor puts a lump sum amount in a debt scheme. He then instructs the mutual fund to transfer a small amount from this debt scheme to an equity scheme every single month at a particular date. So it is a SWP from the debt fund but a SIP into the equity one.

Since the STP works on the principle of redemption and fresh investment, the tax implication would be same as capital gains (short-term or long-term) on the redemption of equity or debt funds.

WHAT IS THE STT?

The Securities Transaction Tax (STT) is levied on the value of a transaction. So when you redeem your units in an equity fund (not debt) or switch them to another scheme, STT of 0.25 per cent will be applicable.

- ValueResearch